Re(FIRB)ishing foreign investment laws before the new FTAs move in

Impractical exemptions to the FIRB regime contained in Free Trade Agreements largely unused yet often overstated

Australia’s general policy towards inbound foreign investment is that it is welcome – in fact it is positively encouraged. That said, certain foreign investment into Australia must first be reviewed by the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) to ensure that it is in Australia’s national interest. Strict review requirements (and their associated fees and administrative costs) are a type of trade barrier and as such, in most sectors, only investments over a certain monetary threshold need to be reviewed. Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) are designed to facilitate international trade by removing tariffs and other barriers to foreign investment for partner countries and they play a significant role in promoting inbound foreign investment into Australia.

Australia is currently party to 13 in-force FTAs. Many (although not all) contain higher approval thresholds under the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act (Cth) 1976 (FATA) for inbound investment from ‘Agreement Country Investors’. The Peru-Australia FTA is the most recent addition to these, having come into force on 11 February 2020 and, like similar treaties, provides higher approval thresholds for investment. Where the purpose of the specific FTA is not to provide investors from that country more freedom to invest in Australia, that can specifically be provided for in the FTA, as is the case in the recent FTA with Indonesia which has not increased the investment threshold.

The real test of the impact of these bilateral trade agreements on Australia’s foreign investment rules will come shortly as a consequence of the long awaited Brexit. The United Kingdom is the third largest source country of foreign investment into Australia[1] and Australia has been tipped as one of the first countries to negotiate a post Brexit FTA.

Despite all the hype around FTAs lowering investment barriers, the higher thresholds are not always as helpful as they may appear. Given the current topical nature of FTAs, it is timely to discuss how Australia’s foreign investment rules reduce barriers to foreign investment for FTA countries and whether they are actually effective.

Breaking down the barriers

Under Australia’s foreign investment laws, FIRB must be notified of all proposed foreign investment before it can proceed, unless an exemption applies or the proposed investment is below the relevant monetary threshold. Various FTAs provide higher thresholds for ‘Agreement Country Investors’ which are defined as an enterprise or national of an ‘Agreement Country’ (an FTA treaty partner). Foreign government investors (such as sovereign wealth funds or government run retirement funds for example) are expressly excluded from the definition.

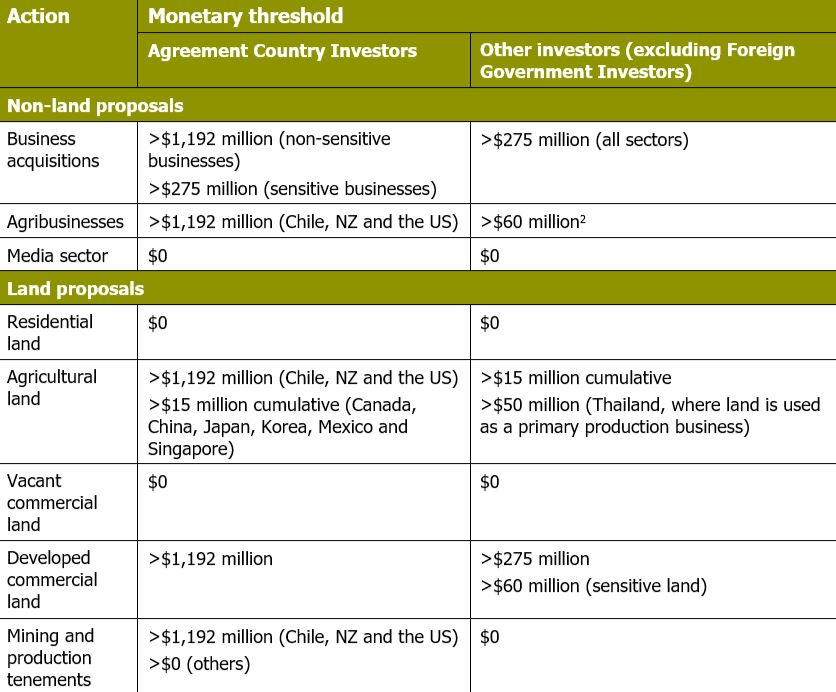

The different FIRB monetary notification thresholds for Agreement Country Investors and other investors are provided in the table below:

As you can see by the above, the difference between the Agreement Country Investor thresholds and the standard thresholds are not insignificant, and can mean the difference between an investor needing to make a FIRB application, pay the application fees and potentially delay a transaction while approval is considered. These factors can mean the difference between a commercial and uncommercial transaction, hence the higher thresholds are often heralded as a win for inbound investment under any FTA.

Is it too good to be true? Yes

While it is clear that Agreement Country Investors are afforded reduced administrative and financial barriers, the higher monetary notification thresholds have limited practical application.

As discussed above, in order to become subject to the higher thresholds, an Agreement Country Investor must be an enterprise or national of the relevant Agreement Country. This effectively means the actual investment entity has to be a resident of, or incorporated in, the relevant foreign jurisdiction.

However, foreign investors will typically establish an Australian investment vehicle, such as a wholly owned Australian registered subsidiary, to conduct its direct investment activities in Australia. The use of an Australian incorporated subsidiary has operational and structuring benefits for any investor but it means that the foreign investor will not meet the definition of an Agreement Country Investor as the newly established Australian subsidiary will not be an ‘enterprise or national of the relevant Agreement Country’. The Australian incorporated subsidiary will be a foreign person because of the tracing rules in the FATA, but as there are no comparable tracing rules in the definition of ‘Agreement Country Investor’ it will not qualify for the higher Agreement Country Investor thresholds.

There are of course exceptions to this general practice of using Australian incorporated investment vehicles. For example, foreign investment into listed entities may well be undertaken directly through the foreign entity. If nothing else, this highlights the problem with the limited definition of ‘Agreement Country Investor’. It should not matter from a policy perspective whether the Australian target is structured in a way that facilitates direct foreign investment.

We can salvage it

In order for FTA countries to actually utilise the higher FIRB notification thresholds, the definition of ‘Agreement Country Investor’ should be broadened so as to include 100% owned Australian incorporated subsidiaries. Only then will FTA country investors gain the benefit of these thresholds without being burdened by the commercial implications of investing directly through foreign entities. Such an amendment would be in line with the apparent policy intent of the FTA’s as the ultimate control and benefit of the investment is the same as if the enterprise or national of the Agreement Country made the investment itself.

The list of Agreement Country Investors is only expected to grow, particularly following Brexit. Therefore, to actually put into practice these policy decisions (the granting of higher thresholds to designated countries), amendments must be made to these largely defunct concessions in order to truly incentivise foreign investment into Australia.

[1] $17.7 billion – according to the most recent FIRB Annual Report 2017-18

[2] Based on the value of the consideration for the acquisition and the total value of other interests held by the foreign person [with associates] in the entity.

For further information on any of the matters raised in this alert, please contact one of the authors listed below:

This publication covers legal and technical issues in a general way. It is not designed to express opinions on specific cases. It is intended for information purposes only and should not be regarded as legal advice. Further advice should be obtained before taking action on any issue dealt with in this publication.