Deal protection – an international comparison

Welcome to Part 2 of our two-part deal protection series. In this article, we’ll explore the United Kingdom and United States’ approaches to deal protection devices.

To review Part 1: deal protection 101, please click here.

How does Australia’s approach to deal protection devices differ to the position taken in the United Kingdom and the United States?

Australia, the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US) are often characterised as having a liberal market, shareholder-centric, capitalist economy although,[1] each has taken a different approach to regulating takeovers.

At a high level, deal protection devices are prohibited in the UK except in limited circumstances, while in the US, directors have the discretion to use deal protection devices subject to enhanced judicial scrutiny. While Australia’s corporate law has tracked closely to the UK model, the Australian Takeovers Panel (Panel or Australian Panel) has not followed the UK’s approach. Australian directors can, similar to directors in the US, use deal protection devices to secure a ‘friendly’ takeover bid and potentially a higher premium provided Guidance Note 7 is followed.

How are takeovers regulated in the UK and US?

In the UK, the Panel on Takeovers and Mergers (UK Panel) administers the Takeover Code (Code). The Code is designed to ensure the equal treatment of target shareholders and that target shareholders are not denied an opportunity to decide on a takeover.[2] The latter principle reflects the notion that the target shareholders, and not the board, ultimately decide whether to accept or reject a takeover bid. Directors are prohibited in the absence of shareholder approval from taking any action that may frustrate a takeover offer or deny shareholders the opportunity to evaluate a bid.

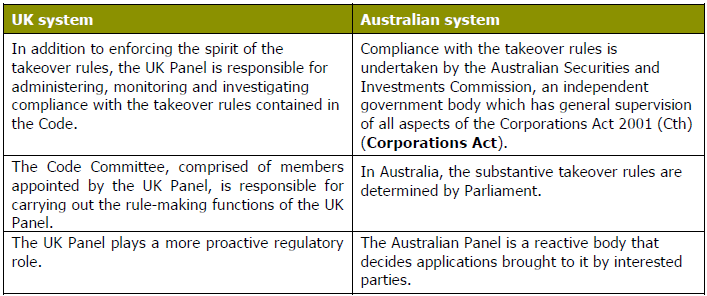

The UK’s model of takeover dispute resolution influenced the transformation of the Australian regime from a court-based system to one centred around a non-judicial body.[3] However, the Australian Panel has a much more limited role than its UK counterpart. For example:

While deal protection devices in Australia are regulated by a non-judicial body, the way the Australian Panel processes applications is in many ways more akin to a court, which is similar to the approach in the US.

In the US, the takeover rules have largely developed through common law derivative suit litigation within the Delaware courts,[4] rather than by a non-judicial body such as in the UK or by Parliament as is the case in Australia. The takeover rules in Delaware allow directors to consider the unique circumstances surrounding each bid to determine if the bid is in the best interests of the company and its shareholders, while holding directors accountable under a fiduciary duty analysis.[5] This is reflective of the notion that target directors in the US have broad managerial discretion. Under Australian law, target directors are not afforded the same degree of autonomy and are constrained by the Corporations Act, ASX Listing Rules and Australian Panel’s guidance.

In many respects, target boards in Australia and the UK act much like gatekeepers, rather than as guardians as is the case in the US, as shareholders must be afforded the opportunity to consider and determine who obtains control of their company. This affects how much scope target directors in each of the jurisdictions have to leverage deal protection devices to encourage a bid and negotiate a potentially higher purchase price.

How does the regulatory environment affect the permissibility of deal protection devices?

UK

In 2011 the Code was amended to prohibit offer-related arrangements, including exclusivity arrangements and break fees, with either the bidder or any person acting in concert with it without the UK Panel’s consent.[6] This prohibition is consistent with the Code’s principle of shareholders not being denied an opportunity to decide on the merits of a takeover.[7]

The amendment also addressed concerns raised by practitioners that deal protection devices left ‘little, if any, room for the board of an offeree company to facilitate or recommend a competing offer, thereby frustrating bids by potential competing offerors’[8] and that target directors had limited power to resist, or negotiate on favourable terms, ‘market standard’ deal protection devices.[9]

The Australian Panel decided not to adopt the UK Panel’s approach to deal protection measures in preference for adopting a principles-based approach encouraging target directors to negotiate such measures and not accept protection measures as ‘market practice’.[10]

US

Deal protection devices have generally been permissible in the US. However, the target board’s decision is subject to enhanced judicial scrutiny beyond the business judgment rule meaning the board is required to establish more than simply a rational basis for its decision. This was established in the case of Paramount Communications, Inc v Time Inc[11] whereby the Delaware Supreme Court determined that the adoption of deal protection devices in implementation agreements are to be subject to a Unocal analysis,[12] which involves a two-prong test:

- The target board’s directors are to first establish that the takeover bid is a threat to ‘corporate policy and effectiveness’; and

- Secondly, that the target’s takeover defence was ‘reasonable in relation to the threat posed’ otherwise known as the ‘range of reasonableness’ test.[13]

These tests are flexible meaning several deal protection devices are commonly used in the US to ensure the consummation of a merger.

A common exclusivity arrangement used in the US is a ‘no-shop’ provision.[14] Unlike the Australian Panel which does not require standard ‘no-shop’ provisions to be subject to a fiduciary out, Delaware courts generally find ‘no-shop’ provisions are reasonable under the Unocal standard provided such provisions are paired with a fiduciary out that allows the board to consider a superior proposal.[15]

Another common practice in the US is the use of break fees. While the UK Panel will only consent to break fees in limited circumstances, such as where a hostile bid has been announced and the break fee is less than 1% of the target’s value based on the competing offer, the Delaware courts treat break fees more favourably. As such, most implementation agreements of US targets include break fees.[16] In the US there is a practice of agreeing break fees significantly higher than 1% of the merger consideration;[17] however, in Phelps Dodge Corp v Cyprus Amax Minerals Co,[18] Chancellor Chandler stated that a 6.3% break fee stretched the definition of being in the ‘range of reasonableness’.

In Australia, under Guidance Note 7, a break fee payable by a target of up to 1% of the equity value of the target is generally acceptable. There have however been instances in Australia where break fees have been in excess of 1% but generally this is limited to circumstances whereby the target is highly geared[19] or deals where the actual external costs for the bidder were likely to exceed the break fee.[20]

Broadly, Australia has adopted a middle ground between the tolerant deal protection regime of the US and the prohibition (with limited exceptions) on deal protections in the UK.

Interestingly, since the 2011 reforms, studies have shown that deal volume in the UK has declined significantly, with no countervailing benefits to target shareholders in the form of higher deal premiums or more competing bids.[21] This illustrates the potential role that deal protection devices can have in encouraging and securing a bid from bidders by providing some comfort to bidders that if they take the high-stakes risk of a public takeover, they will get some protection, if, as can happen, another bidder ends up getting the deal, the regulators say no, or the target’s shareholders choose not to accept the offer. Put another way, the absence of deal protection devices could cause a bidder to offer a discounted price to account for the risk of non-consummation of the deal.

Therefore, while Australia, the UK and the US are often characterised as having similar economies, each have different approaches to the regulation of takeovers and, in turn, deal protection devices.

Conclusion

Deal protection devices, such as exclusivity arrangements and break fees, are common features of control transactions involving Australian target companies. The Australian Panel provides guidance as to their acceptable use at both the non-binding and binding bidding phases to ensure such devices do not inhibit the acquisition of control taking place in an efficient, competitive, and informed market.

This approach differs from that in the UK and the US. In the UK, directors are prohibited from using deal protection devices except in limited circumstances on the basis that such devices prevent shareholders from deciding on the merits of a bid. In the US, directors are provided with broader managerial discretion which reflects the notion that US directors are guardians of shareholder interests, rather than merely gatekeepers for shareholders. By empowering directors of target companies with deal protection devices, directors of Australian and US target companies have more flexibility in the way they can seek to generate greater value and premiums for shareholders than their UK counterparts.

M&A is a dynamic field and the Australian Panel’s guidance will need to continue to evolve to address new creative deal protection tools developed by bidders.

[1] Mitchell, Richard et al, ‘Shareholder Protection in Australia: Institutional Configurations and Regulatory Evolution’ (2014) 38(68) Melbourne University Law Review 68, 70.

[2] Takeover Code, s 2(a) and General Principle 3.

[3] Corporate Law Economic Reform Program, Takeovers, Proposals for Reform: Paper No 4 (CLERP 4) (Canberra, Australian Government Publishing Service, 1997), 32.

[4] Saulsbury, Chip, ‘The Availability of Takeover Defenses and Deal Protection Devices for Anglo-American Target Companies’ (2012) 37 Delaware Journal of Corporate Law 115, 118.

[5] Saulsbury, n 4 at 128.

[6] The Takeover Panel Code Committee, Review of Certain Aspects of the Regulation of Takeover Bids, Publication of RS 2011/1, 2011/18 (Panel Statement, 21 July 2011); The Takeover Panel Code Committee, Instrument 2011/2, Amendments following the Code Committee’s review of the regulation of takeover bids (Instrument, 21 July 2011) 1, 32.

[7] Saulsbury, n 4 at 154.

[8] See The Takeover Panel, Consultation Paper Issued by The Code Committee of The Panel, Review of Certain Aspects of The Regulation of Takeover Bids, PCP 2010/2 (Consultation Paper, June 2010) 80 (“PCP 2010/2”).

[9] Saulsbury, n 4 at 156; See PCP 2010/2, n 8.

[10] Re GBST Holdings [2019] ATP 15, [35].

[11] 571 A.2d 1140 (Del, 1990) (“Paramount”)

[12] Paramount, n 11 at 1151.

[13] See Unocal Corp v Mesa Petroleum Co 493 A.2d 946, 955 (Del, 1985).

[14] Saulsbury, n 4 at 147.

[15] Saulsbury, n 4 at 148.

[16] Saulsbury, n 4 at 148.

[17] See Saulsbury, n 4 at 149; see also Fernán Restrepo and Subramanian Guhan, ‘The Effect of Prohibiting in Mergers and Acquisitions: Evidence from the United Kingdom’ (2017) The Journal of Law & Economics 60, 103.

[18] 1999 WL 1054255 2 (Del, 1999).

[19] See, for example, Re Webcentral Ltd [2020] NSWSC 1279.

[20]See, for example, Re Ausdoc Group Ltd [2002] ATP 9.

[21] Fernán Restrepo and Subramanian Guhan, n 17 at 106.

This publication covers legal and technical issues in a general way. It is not designed to express opinions on specific cases. It is intended for information purposes only and should not be regarded as legal advice. Further advice should be obtained before taking action on any issue dealt with in this publication.